The beginning of Modernism in art and design was inspired by the idea of designing good things. This concept was formulated most clearly at the Bauhaus (1919–1933). A “good” object was sleekly simple and functional.

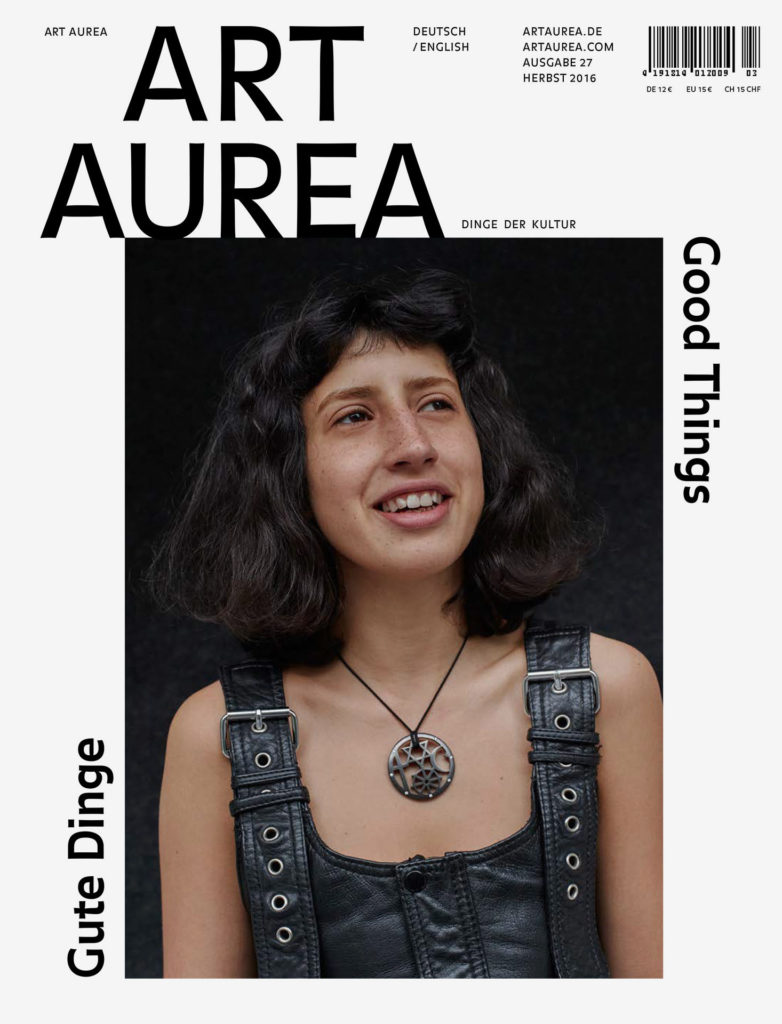

Cover of Art Aurea 27: Model Su with Unita pendant by Corinna Heller. Black rhodanized silver, 8 brilliants. 1.100 €. Photo Laurens Grigoleit

Ornamentation and eclecticism were regarded as useless veils and dishonest masquerades. Function alone should determine the aesthetic of houses, rooms and utilitarian objects. This was associated with the effort to offer a better quality of life to all classes of society. The design academy in Ulm (1953–1968) and many other schools of design revived this idea, which remains valid today, as was recently shown by the exhibition Alles ist Design (Everything is Design) at Vitra and at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn. But in the meantime, the fundamentals have changed. Never before—at least, not in modern democracies—have individual freedoms been more highly valued than they are today. Formal dictates such as those which Max Bill postulated in 1957 in his book Die gute Form (The Good Form) were already obsolete by the end of the 1960s. People who like playful or ornamental styles can be happy with this.

Jewelry artist Gitta Pielcke protests against animal abuse. Photo Ulrike Myrzik (detail)

Two billion people inhabited our planet a century ago, but our globe teemed with 7.35 billion humans in 2015. This sheer number compels designers, producers, politicians and all of us to rethink things. Every product made of plastic, which pollutes the oceans, is bad. Whatever cannot be repaired and is used for only a short time is bad. According to a Greenpeace study, two billion pieces of clothing hang unworn or seldom worn in closets and cabinets in Germany alone. It’s bad when the per capita ecological footprint in Germany is ve hectares. If everyone lived this way, we would need 2.6 Earths. An ecological footprint of 1.7 hectares would be equitable.

Ritsue Mishima’s studio in Venice. Photo Oliver C. Haas (detail)

Several articles in this edition show concrete ways in which designers and artists try to shoulder ecological responsibility. For example, Gitta Pielcke, whose jewelry campaigns against the factory farming of chickens. Or the young fashion designer Elke Fiebig, who dedicates herself to slow fashion. The architect Philippe Rahm takes ecological and economic considerations into account in his projects. Ritsue Mishima is active in the eld of art with her glass objects, as are the Campana Brothers and Christopher Duffy with their furniture. Design auctions clearly show that things which uphold high artistic and craftsmanly standards defy short-lived consumption and last for generations. Critics say, “Only a few people can afford such things.” But that’s only partly true. Very many people could buy fewer things, but better things. Not everything that’s costly is automatically good: here too, it’s important to differentiate. But the craze for cheapness is ultimately most costly for us, our children and our environment.

Swing Table by Christopher Duffy. Certified wood, powder-coated soft steel. £7,880 ex. Vat

Text Reinhold Ludwig