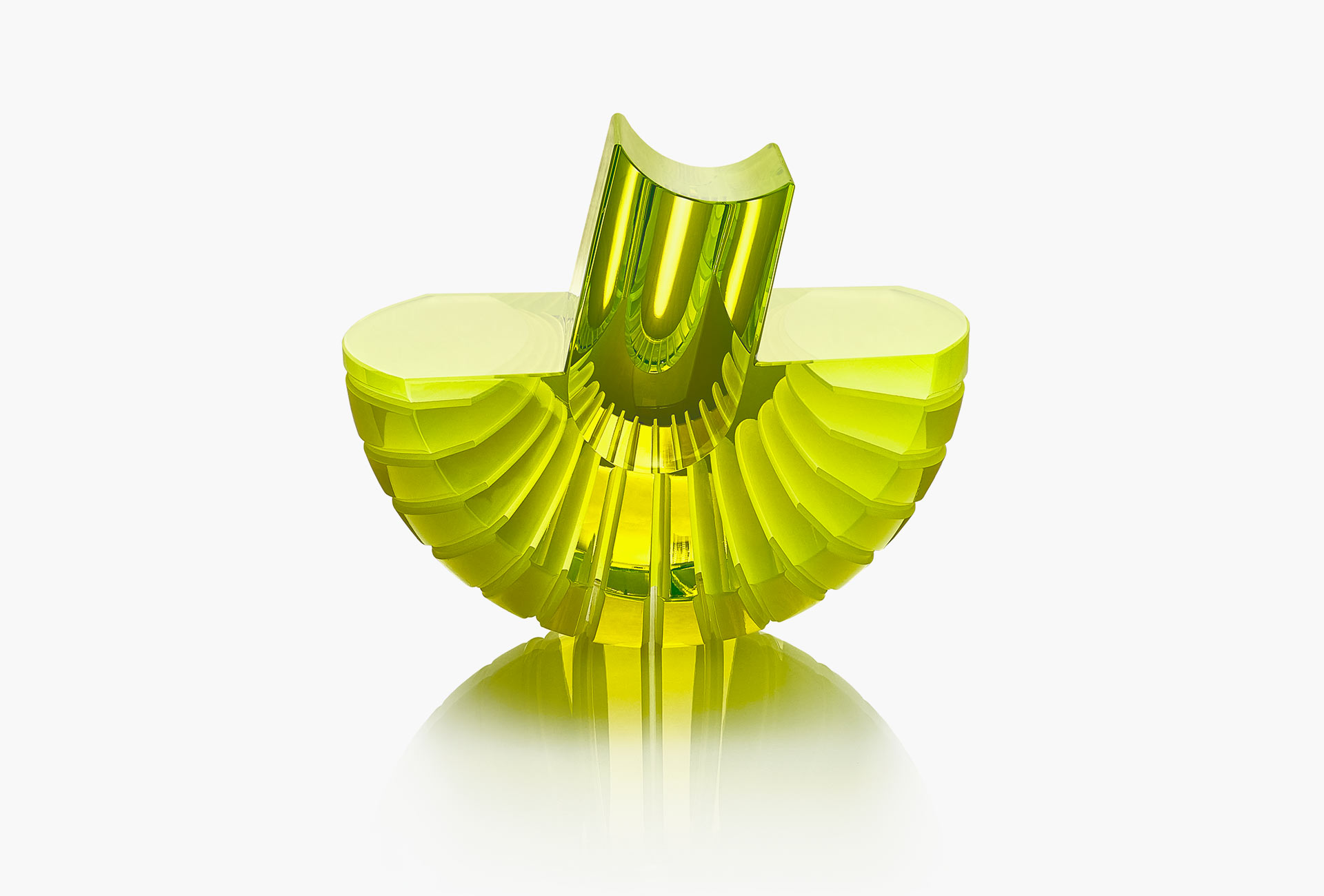

Barbara Nanning, Firebird, 2018. 46 x 34 x 28 cm. Photo Tom Haartsen, The Netherlands.

Born in The Hague in 1957, Barbara Nanning studied ceramics at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam four decades ago. Since then she has developed into an internationally renowned artist whose works are represented in numerous museums and private collections in the Netherlands and abroad. Nanning achieved fame with her unconventional ceramic objects and installations. For the past 25 years, she has also devoted herself to glass art.

Art Aurea What prompted you to concentrate on ceramics during your art studies 40 years ago?

Barbara Nanning As a 10 year old qirl I already turned small shapes on a shovel disk on street art fairs. I wanted to work with clay and other materials from an early age and make beautiful refined products.

AA Could you describe the Zeitgeist of the era during which you studied in Amsterdam in the 1980s? What expectations did you have for your studies at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie?

BN My study period was in the transition phase of tableware, which were then produced in ceramic factories, and the beginning of small private studios. The tendency at the academy was to make tableware by hand turning and casting in plaster molds. At that time you chose one department and there was little to no space for using and combining various materials in one product. My expectation was to first learn the techniques well and to be able to combine various materials in efinitely in order to achieve the desired end result.

AA Did you have any role models? And what did you want to do differently?

BN I was not interested in the Dutch teaching of concentrating on making functional consumer goods. My role model was the Dutch artist Harm Kamerlingh Onnes (1893–1985). He made drawings, watercolors, gouaches, oil paintings and ceramics. Harm Kamerlingh Onnes is best known for the small, humorous character sketches of everyday life in the form of painted tiles, animal and human figures. The narrative element of his work really appealed to me. I also wanted to visualize my story in plastics and in spatial forms. In America simultaneously was the West Coast Ceramics (1956–1986), the movement from ‚designer-craftsman‘ to ‚artist-craftsman‘. I found this much more interesting and felt like an eye opener.

Barbara Nanning, Beneath the Water, 2019. 27 x 27 x 11 cm. Photo Tom Haartsen, The Netherlands.

AA You first worked with glass after an invitation from the National Glass Museum and the Royal Leerdam Glass Factory in 1994.

BN During realising my monumental projects for public spaces I learned to known the force and power of excellent craftsmen. Thanks to the good cooperation and excellence knowledge and craftsmanship of master glassblower Henk Verwey and master grinder Eddie Bek at the Royal Glass Factory Royal Leerdam objects immediately resulted at a higher level.

AA You have been working with glass for 25 years. Many of your objects and installations seem to have “grown spontaneously” and remind us of organic forms. What is the source of your penchant for the organic? What do you want to express with it – apart from the interesting form per se?

BN In my works I want to express the growth and the endless movement of life. I always work from the circle, it is a primal form. The movement comes from the resting point in the middle. Nature, both organic and inorganic, is my constant source of inspiration. I study crystals, jellyfish, flowers and micro-organisms from an almost nineteenth-century fascination with form, structure and geometry. I connect tradition with innovation, Eastern wealth with Dutch austerity, freedom with structure and reason with feeling. A fusion of carefully chosen and sometimes seemingly contradictory elements that ultimately looks so obvious that no one is surprised at the unusual combination of ingredients.

AA In the German-speaking world, art objects made of ceramics or glass are usually considered to be handicrafts or examples of the applied arts. How do people in the Netherlands judge this? And how do you deal with it today?

BN In the Netherlands, works made of ceramic and glass often fall under the term Free Design. It is not Art and not Design. In my opinion, there is often a difference in the starting point of artists and Free Designers”. The idea, the concept, is the most important thing for artists. The material chosen is the most suitable for theit ideas. “Free Designers” have a preference for a specific material and they often think from their material.

Barbara Nanning’s glass objects are created in collaboration with Czech glassblowers.

AA You create your glass objects and sculptures in collaboration with Czech glassblowers. How do you evaluate the role of craftsmanship in the artistic process?

BN Long before the actual realization, I discuss at length my ideas and sketches with the glass blowers, cutters and assistants. The day before, we go through the plan one more time, and then the process begins. Throughout this collaboration, the blowers, cutters and assistants are an extension of the designer.

AA Kunstmuseum Den Haag honored you with a retrospective exhibit from August 31, 2019 to March 1, 2020. What did this show mean to you? And what were the responses to it?

BN I was born in The Hague. The retrospective exhibition of 40 years of work in the beautiful architectural Art Museum The Hague (architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage in close collaboration with Van Gelder) was a long-cherished wish of mine. The exhibition has received a lot of attention internationally and the Kunstmuseum said that an exhibition has never been photographed so much. This exhibition and the simultaneously published book Barbara Nanning – Eternal Movement was a gift, it felt as a crowning achievement of my hard work.

Co-production Barbara Nanning & Aleš Zvěřina, Chimaera, 2020. Uranium glass. 22 x 18 x 19 cm. Photo Jiří Vlášek, Tschechien.

A monograph was published to accompany the retrospective exhibit “Barbara Nanning – Eternal Movement. Ceramics, Installations and Glass Art” at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag from August 31, 2019 to March 1, 2020. The 144-page hardcover volume is available for €25.00 (ISBN 978 94 6262 256 2)