The ceramic artworks by Margareta Daepp, who was born in Bern in 1959, that are on display at the Musée Ariana may seem at first glance like examples of reduced, functional product design. But in reality, many of these pieces pose questions, for example, about form as a bearer of meaning, memory or aesthetic norms. In addition, this Swiss artist’s frequently monochrome creations combine Near Eastern and Far Eastern concepts with minimalist Western ideas. “Her artistic universe is characterized by silence, austerity, poetry, color, emptiness and space.” The statement from the museum in Geneva adds that her works are of impressive clarity, lively, yet simultaneously also serene and calm, the result of an enlightened and uncompromising artistic path.

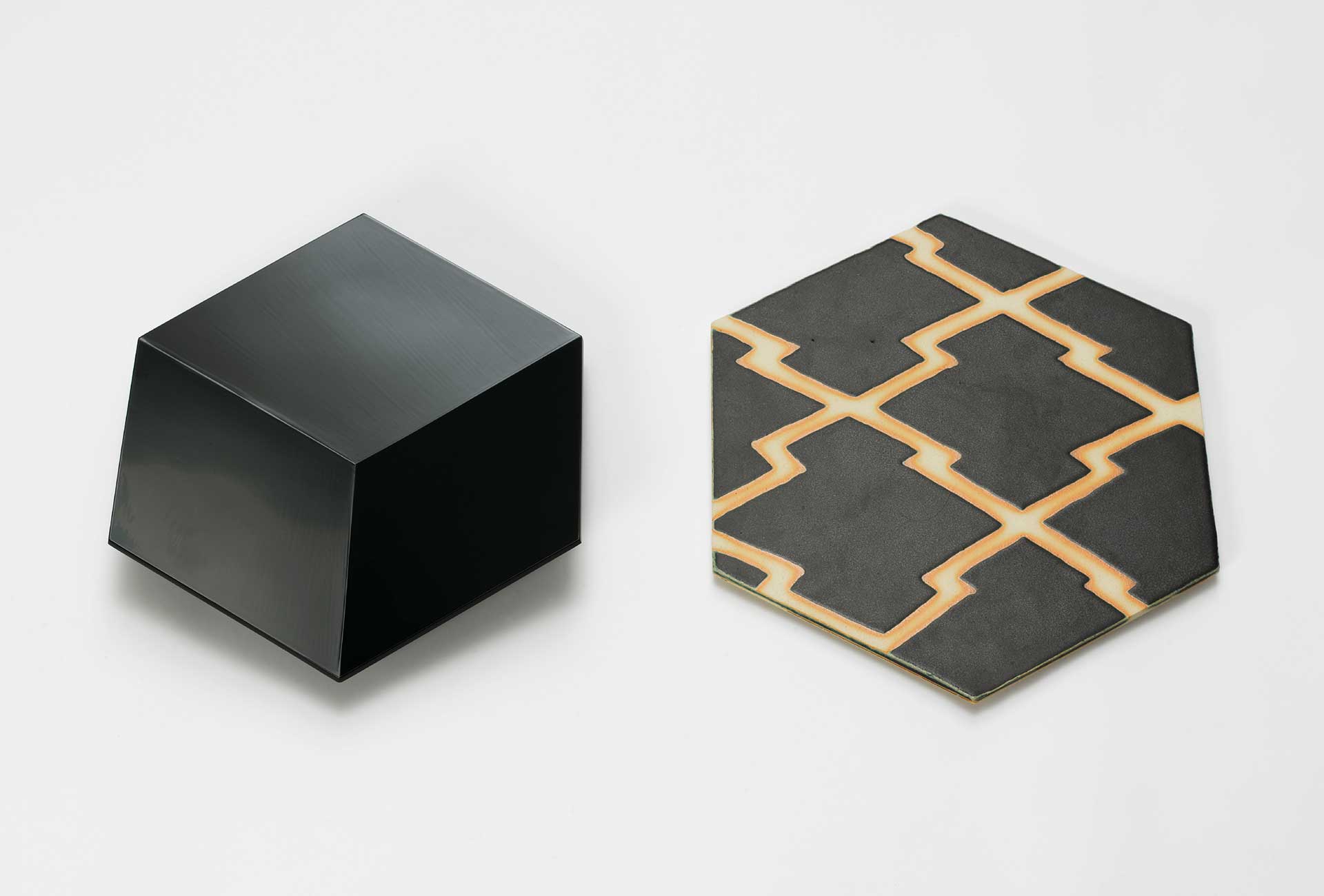

Hexagon 1 Seto, 2013, from the series Oribe, wood and Urushi lacquer, 30.8 × 35.7 cm, h 6 cm. Hexagon 2 Seto, 2013, from the series Oribe, stoneware, Oribe glaze 34.2 × 39.5 cm, h 1.5 cm. Photo Dominique Uldry.

Anne-Claire Schumacher, chief curator at the Musée Ariana, explains that while attending the preliminary course (1976-77) at the School of Design in Bern, Margareta Daepp quickly realized “that the third dimension is crucial for her.” This is why she chose the ceramics class over the graphics class. Margareta Daepp’s artistic interest was sparked by Philippe Lambercy (1919-2006), who headed the ceramics department at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs de Genève and was instrumental in overcoming traditional artisanal and industrial boundaries in ceramics. After receiving her diploma in Bern in 1981, she enrolled at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs in Geneva, where she met the Japanese ceramic artist Setsuko Nagasawa, which was born in Kyoto in 1941. Schumacher writes: “Everything is different here: the working of the clay, the view of the material and the handling of the proportions. The young artist is fascinated by Nagasawa’s direct and frontal confrontation with the material, as well as her thoughtful and precise manual interventions, which cannot be touched up afterwards.” Margareta Daepp discovered ceramics as a living material.

Pink flower on square, Bern, 2016, from the series Poetic pictogram. Porcelain, colored, enamel. Square: 30 × 30 × 1 cm, flower ø 19,5 cm, h 7 cm. Collection of the artist. Photo Dominique Uldry.

Her studies in Geneva were followed by work in her own studio, which she opened in Bern in 1984. But Margareta Daepp began another course of study in 1989, this time with Rebecca Horn and Isa Genzken at the Berlin University of the Arts. This was followed by an artist-in-residence fellowship from the EKWC in ’s-Hertogenbosch and a stay in New York from 1994 to 1995. Still fascinated by Japan, Margareta Daepp traveled to the Asian archipelago several times between 2005 and 2017, three times as artist in residence and to Kyoto and Osaka for exhibitions. “Among the most formative experiences is firing in an anagama kiln [a horizontal kiln with direct exposure to flame] and the collaboration with lacquer specialists,” Anne-Claire Schumacher explains. As fascinated as Margareta Daepp is by Japanese culture, she is careful not to succumb to fascination with her role models. She has used the inspiration of Japan first and foremost “to push the radicality of her own artistic statement further, without losing her own language.” The first exhibition room at the Musée Ariana is dedicated to Margareta Daepp’s Japanese works, while “in the second room, she engages with space in an expanded sense, testing unknown paths and opening up new perspectives.”

Archéologie du future, 1993, terracotta embossing, 36 × 120 cm, h 59 cm. Collection of the artist. Photo Dominique Uldry.

In the essay “Absorbing Meaning and Transporting Meaning – On the Vessel Art of Margareta Daepp,” Susanne Schneemann writes: “The aesthetics of the industrial form is a phenomenon beyond nostalgia – Margareta Daepp has been questioning its topicality for more than thirty years.” As her first example, the art historian uses Daepp’s “Archaeology of the Future,” a series of large canisters that she molded in clay in 1993: “The fired and unglazed ceramic vessels with their huge volume have an opening and a lid – but both are glued together. They are bulky and they seem functionless: Are they also without meaning?” The industrial form that Margareta Daepp references with her canisters can be reduced to the central dogma of design history, “form follows function,” or supplemented with a more current “form follows emotion.”

Exhibition view. The formal clarity of Japanese architecture is also found in Margareta Daepp’s vessels. © Musée Ariana Geneve. Photo Boris Dunand.

- —

-

Musée Ariana

Avenue de la Paix 10

CH-1202 Geneva, Switzerland - Link