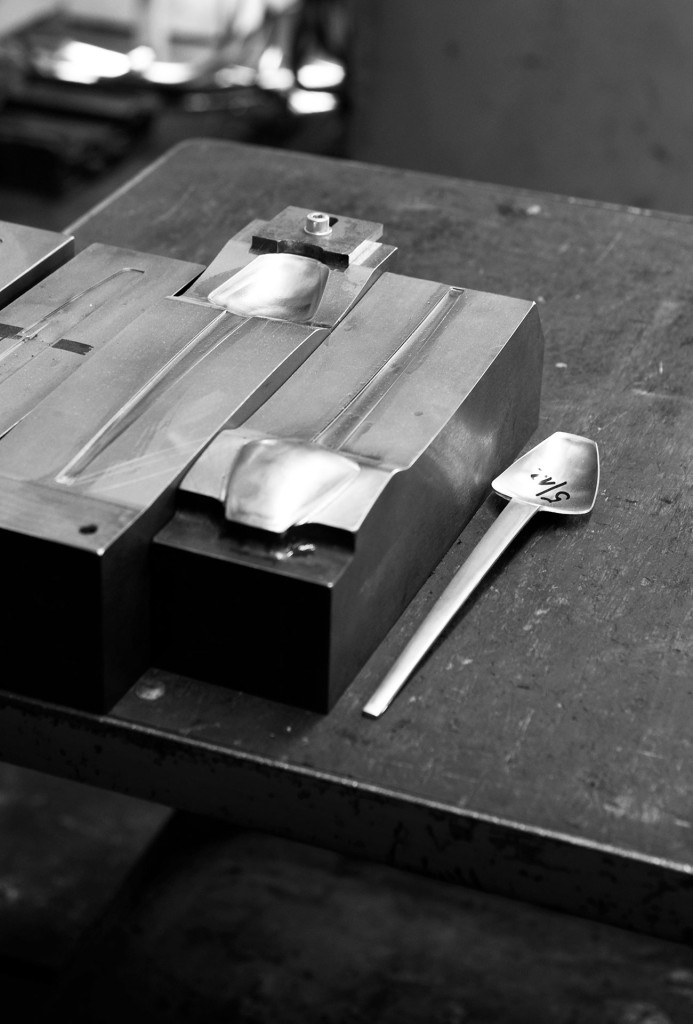

Artisanal production at Augarten, Vienna. Vessel from the Shortcut table service. Design Thomas Feichtner

The biggest event in Thomas Feichtner’s life was not his graduation from the Universität für Künstlerische und Industrielle Gestaltung [University for Artistic and Industrial Design] in Linz 1995, but a subsequent motorcycle trip through half of Europe. The experiences he had on that journey and his direct contacts with so many people during the excursion continue to enrich his life today, recalls the designer, who hosted the author at his studio in Vienna’s 7th district, a neighborhood enlivened by the presence of many creative individuals. Born in Brazil in 1970 and brought up in Düsseldorf, Feichtner is presently professor of product design at the Muthesius Kunsthochschule [Muthesius Academy of the Arts] in Kiel. His successes are chronicled on his long list of commendations and past clients, which include renowned Viennese establishments such as the Wiener Silber Manufactur, J. & L. Lobmeyr, Porzellanmanufaktur Augarten and Neue Wiener Werkstätte. Feichtner also designed items for Thonet and Carl Mertens.

A Viennese Pot is the title of a teapot that he designed in 2008 for the Wiener Silber Manufactur, which manufactured the vessel in a small series. More like a constructive sculpture than an object for daily use, this artifact opposes the “form follows function” design edict, with which Feichtner disagrees: “Design isn’t solely justified by its purpose, but also expresses the joy and zest of form.” He tries to convey this passion to future designers: “If I asked a student, ‘Why did you design this object in this particular way?’ and he answered ‘Because I like it this way,’ I would be wholly satisfied with his explanation. This also applies to practical applications. “I recently had a student who insisted that he simply must cast brass. Molds were accordingly constructed and the molten brass was poured. It was our first attempt with this material, but it was a terrific experience.” Feichtner advises his students to integrate craftsmanship into their studies of design because this will help them to find ideas or concepts. Handcraftsmanship was totally ignored during his own student years when he studied to become an industrial designer. Only afterwards did he discover how exciting and enriching it is collaborate with craftspeople. For example, when he works on a new project at a silver manufactory with someone of retirement age who had begun learning the silversmith’s craft at age fifteen in the selfsame workshop, “then sparks fly, I feel a tingle, there’s energy, esprit, fun….”

On a trip to China shortly after the turn of the millennium, Feichtner decided to turn away from industrial design in the field of investment goods and to turn toward designing for manufactories and workshops. He had come to China to find Asian customers for the sporting goods industry. Many designers, he recalls, had set up agencies in Shanghai at the time. All of them had told him, “Go to China. The streets there are paved with gold. And you’ll have infinitely many possibilities.” But the gold-rush fever proved deceptive. Feichtner soon realized that this wasn’t a journey to acquire new customers, but a trip to document the prevailing situation: child labor, adverse working conditions and enormous environmental pollution. Feichtner was an eyewitness to all this. “I thought to myself: When I get back to Europe, I’ll look for someone in my own street, in my immediate neighborhood, even if he’s just a little carpenter, and I’ll collaborate on a project with him.” It had suddenly become clear to Feichnter that a designer isn’t only a solver of problems, but can also be their cause.

To oppose the dangers posed by globalized work processes that completely separate designing from manufacturing, Feichtner launched a counteroffensive which continues to the present day. He turned down offers to design chainsaws and drilling machines because “the only thing I still wanted to do was to combine my form-giving with something artisanal, to produce something in my immediate surroundings and let that develop into a partnership which would be more like a friendship, a sharing of mutual interest or curiosity, rather than a promise of profits for both parties.” In the process of creating these artifacts, Feichtner would sit beside the silversmith and helped him polish, file or experiment. “That had a totally different quality for me and suddenly I felt happy again.” Feichtner has collaborated ever since with craftspeople to develop chairs, drinking glasses, fruit bowls and vases, a saliera (saltcellar) for the 21st century and a bangle with golden geometry. “My family lives with my furniture. My nephews eat with my cutlery and my flatware. This means that I have a direct influence on my daily life. And that’s important to me.” Instead of CAD programs and rapid prototyping, Feichtner needs nothing more to create his designs than a pencil and a sheet of paper. Carrying the sketch in his hand, he walks across the street to the model-builder’s workshop or directly into the manufactory. No matter whether the question is the thickness of the sheet metal for future cutlery or the character of a porcelain vessel before it’s fired: nothing would be possible without the expertise, knowledge and skills of a master craftsperson.

Feichtner profoundly respects the know-how that he encounters in these workshops. But it isn’t only the craftsmanly tradition that impresses him. He’s even more impressed by the “smaller yardstick” that enables a person to work more freely and to experiment with a partner: “When I look at other designers, I often get the feeling that they’re chasing life without ever catching it.” But working with neighboring artisans, Feichtner says, gives him a chance “to deeply inhale life itself.”

By Susanne Längle

The product designers webpage

First published in ART AUREA 2-2014