There was a time when the word “design” had an almost magical sound. Good form in Germany’s post-war era was primarily associated with the hope of renewing the country after the horrors of the Nazi era, of dusting off its past and making things better. Later, starting in the 1980s, design became an expression of a progressive lifestyle. Names like Dieter Rams, Richard Sapper and Jasper Morrison, not to mention those of star architects like Richard Meier or Tadao Ando, were spoken with admiration and sometimes even with reverence. This attitude continued through the “golden eighties,” when Italian postmodernist designers sought to impress the worlds of architecture and furniture design with bright colors, little spheres and tall turrets. The New German Design movement made waves in the BRD with satirical, arty and sometimes kitschy creations. Leading Central and Northern European designers, on the other hand, pursued an aesthetic of sleek simplicity.

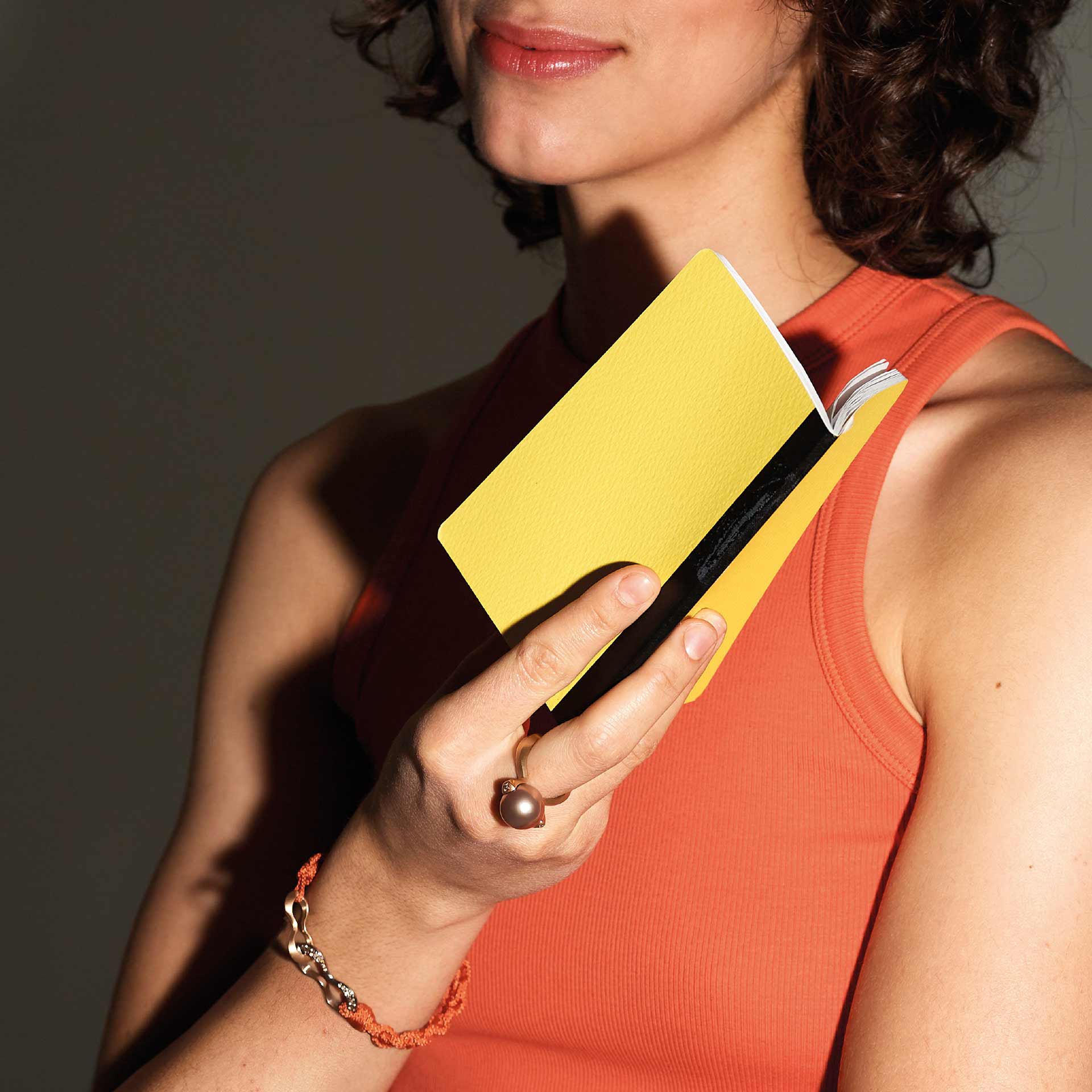

Corinna Heller, pearl ring Achter. Ming pearl, 750 rose gold, sapphires. Bracelet Achter. 750 rose gold, 750 white gold, natural cinnamon diamonds, cord. Photos Brigitte Häussermann. www.corinnaheller.de

Angela Hübel, Regatta ring. 750 gold, garnet. © Angela Hübel. www.angelahuebel.de

Johanna Otto, Creole Cambio. 750 yellow gold, available in two sizes. www.johannaotto.de

Oliver Schmidt, La Linea earrings. 750 yellow gold. www.ol-schmidt.de

Vera Rhodius, earrings. Glass, fine gold-plated silver, Inhorgenta, Hall B2, Booth 141. www.vera-rhodius-schmuck.de

The design euphoria also reached jewelry in the latter decades of the 20th century. The ambition of the new jewelry designers in Europe, increasingly many of whom were women, was not merely to improve design, but also to overcome the “soulless” production methods and materialistic mindset that generally prevailed in the jewelry industry. Added to this was the need to revitalize traditional goldsmithing techniques in workshops. Technical colleges and universities played a crucial role in this as thinktanks for the further development of modernist ideas in art, architecture and product design. The foundation for all jewelry designers was the maker’s own authentic design language; copying was absolutely forbidden. Short-lived trends, as are common in the fashion industry, were rejected.

The new jewelry-makers who emerged in the 1980s also had no intention of creating superficial or decadent luxury items. Their focus, then as now, was on production in authentic workshops, masterful craftsmanship and small series. The one-sided emphasis on material value and the myopic view of jewelry solely as a status symbol became obsolete. Role models for this new design language were jewelry artists and professors such as Sigurd Persson (Sweden), Friedrich Becker and Reinhold Reiling (Germany) and Emmy van Leersum (Netherlands), to name just a few important figures.

Jutta Ulland, clip from the series Windungen und Wendungen (Twists and Turns). 925 silver, 925 silver gold-plated and 750 gold. Inhorgenta, Hall B2, Booth 336. www.jutta-ulland.de

Pura Ferreiro, Owl earrings. 925 silver, blackened, and 900 gold, granulated. www.puraferreiro.de

Manu Schmuck, O1054PE drop earrings. 925 silver, 900 gold, with pearls. Photo: Pixelgold. Inhorgenta Hall B2, Booth 129. www.manuschmuck.de

Munich’s Inhorgenta was the leading and preeminent trade fair for jewelry designers. This marketplace made a name for itself internationally, especially thanks to its outstanding design segment. The presence of individual designers at the fair was further enhanced by a number of sophisticated German jewelry manufacturers. Dealers from all over Europe and even overseas were attracted by German jewelry design. When the new fairground opened its doors in Munich-Riem in 1998, jewelry design presented itself proudly and confidently in Hall C2. Complemented by vocational schools and special exhibitions, Inhorgenta was unique among jewelry trade fairs worldwide.

At that time, the new jewelry design was already visible in specialized galleries, progressive goldsmith workshops and at a considerable number of renowned jewelry stores. This remains true today, although for many reasons the market has become more challenging for all jewelry manufacturers. Inhorgenta had already experienced a steady decline in the presence of sophisticated designers over the previous two decades. Even leading studios like Angela Hübel and Georg Spreng, who had long since moved their presentations into Luxury Hall B1 (now called Fine Jewelry), have not been represented at Inhorgenta for several years. Young talent has been scarce in jewelry design these past few years, but that’s another story.

As always, jewelry designers still strive to offer an honest and sustainable alternative to mass-produced industrial goods, which for many years have often been imported from the Far East. In addition, they usually use recycled gold or gold from fair-trade sources. These are strong arguments in favor of contemporary jewelry design, which, when it is presented convincingly, has lost none of its fascination. Reinhold Ludwig

- —

-

Inhorgenta

Messe München - Link