Christof Lungwitz and his wife, a physiotherapist, live in the picturesque town of Leichlingen near Düsseldorf, in a house perched on a hillside and fitted with mahogany doors, mosaics, etc. “At first, I had a screaming fit,” remembers this minimalist, who was born in Weimar in 1948. But meanwhile he enjoys living amongst these things. “I am living a contradiction,” he says. For several years now, he has been designing puristic objects with names such as “Bowl for Ideas” or “Angular Tray for a Shyster”. He intuitively comes up with these poetic names while working on an object. Lungwitz made a name for himself in the 1990s with his limewood cabinet, whose top elements feature the naturally grown irregularities of the original tree trunk. Almost every day, he descends from his office in the attic to his machines in the basement. His tidy workshop is small, and the shelf units at the walls, filled with tools, different types of timber and collected objects, almost reach the ceiling. His melancholic eyes sparkle with enthusiasm when he thinks of his next project: “chamber of wonders cabinets – I already have the objects that I want to put into them.” (Read on below)

To Christof Lungwitz’s profilewith further objects

This avid collector has developed a fervent passion for combining curiosities that originally don’t belong together, also in the form of still lifes. This focus on the figurative – also in smaller formats – will no doubt be something new for connoisseurs of Lungwitz’s work. A platter featuring an arrangement of wooden objects that he painted in white – a cactus, a pear and a few apples – testifies to his new predilection. He also collects toys, and his latest purchase is an old dollhouse. Do we go back to our childhood when we grow old? “To some extent, yes. My father, a sculptor, was rarely at home, and we had hardly any toys.” He points to a few books about his father, whose covers he helped to create. “His creations can be found in many public places in the Ruhr region. It took a long time for me to get over that.” He quickly changes the subject to his current work, speaking with care and passion (“fantastic” is one of his favorite words) – qualities that can also be sensed in his objects.

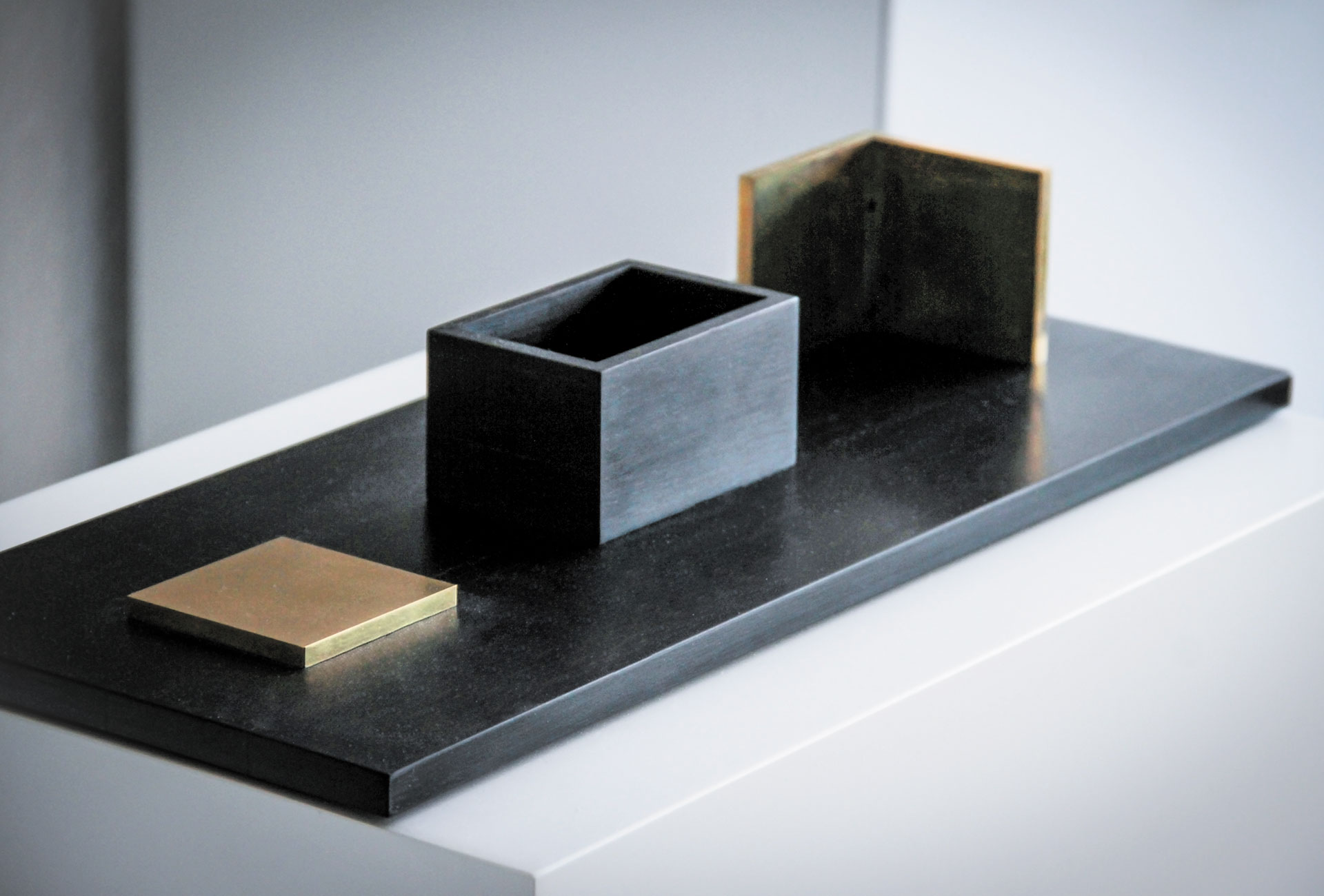

Lungwitz prefers working in the daytime, but it also happens quite often that, while having some (or occasionally too much) red wine and listening to Kraftwerk or Pink Floyd (occasionally too loud), he mulls over a piece until midnight. Before they leave his workshop, he observes each of his creations for days and sometimes even weeks in all kinds of lighting conditions. When he crafted the “4×8 equals 32” object from Makassar ebony, he cut the model’s base plate umpteen times, each time put the appropriate objects on it and checked the proportions, which, according to him, are crucial. Just as we don’t feel comfortable in a badly proportioned room, he explains. This is not a problem at his desk, where he has a view of flower and vegetable beds and is surrounded by furniture he designed himself, and thus works in an environment that is conducive to dreaming, drawing sketches and philosophizing.

Lungwitz only reads what’s absolutely necessary. He prefers to indulge in coffee table books. He has a penchant for African and Indonesian woodwork, and for the fine arts: Tony Cragg, Donald Judd, Cy Twombly and Picasso, but only the latter’s sculptures, “and the rather unknown Diego Giacometti, who created unbelievably beautiful furniture.” He particularly likes working with wood “that communicates something”, like the purple amaranth wood. Using exotic woods is actually not ethical, he admits – and the inner conflict shows on his face. “But the inimitably black color and fine pores of ebony are simply unrivaled.”

Although he also uses brass and bronze, Lungwitz has had a deep affinity for wood ever since he trained as a cabinetmaker. But this rueful school dropout also inherited the love for this natural material from this father, who talked him out of studying interior architecture saying “What do you want with this crap?” After his training, he was persuaded by his brother, who is also sculptor, to study graphic design and visual communication. Fate struck shortly after his graduation, when Lungwitz had an accident and his lower arm was cut right down to the bone. He had to spend long periods in the hospital, and some of his fingers are still deformed. But the accident inspired him with the idea to design furniture and objects.

In the 1980s, when the first PCs emerged, he opened an interior architecture firm. Lungwitz’s face clouds over when he tells us: “My aspirations didn’t exactly facilitate things in financial terms.” But people’s asking “can’t you turn this blue real quick?” is unacceptable, he emphasizes. Of course you can create bowls using CNC mills, he says, but he doesn’t want to work like this, without any emotions involved. “I create one-of-a-kind pieces, not series, with the exception of the limewood cabinet,” he explains.” But each of the nine variants’ tops are different,” he stresses. And his approach has paid off: he was awarded a prize by the Wüstenroth foundation for the interior of his wife’s practice.

The technological “progress” at Düsseldorf University, where he teaches twice a week, is something else that rankles with him. The students forget the skirting boards when they design things on the computer, he says, and it’s shocking to see how superficial they are. They don’t have enough knowledge and practical background, and many don’t even know how to draw freehand, he deplores.

But he can’t make a living from his art alone either. Attending trade fairs is expensive and useless, he says, and “there’s always somebody who creates some kind of extremely low-quality felt hats and bags.” He has nothing against fashion, but his idea of good craftsmanship is associated with names like Raf Simmons, Yohji Yamamoto or Vivian Hackbarth. He also finds the trade fair visitors difficult to deal with. In Düsseldorf, a woman once told him indignantly that she would have crafted one of his bowls very differently. There won’t be any discussions like this at the Craftcontor shop-cum-gallery in Bonn that represents him. This is why he’ll be prioritizing galleries in the future. The market for objects that bridge the gap between the fine and applied arts is difficult, but Lungwitz is proud of his oeuvre: “I simply say, ‘these are my creations, take a look at them’, and that’s it.”

Text Agata Waleczek Photos Judith Büthe

English translation Sabine Goodman